The Stolen 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari Violin Emerges

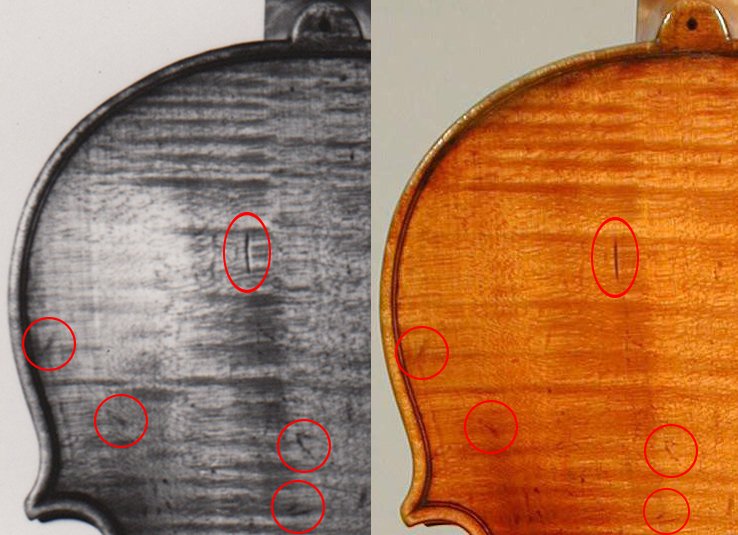

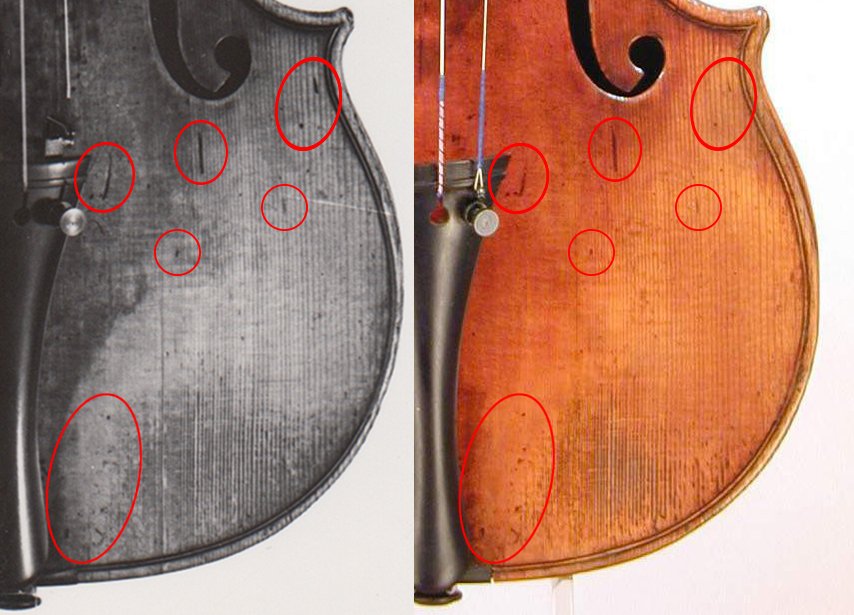

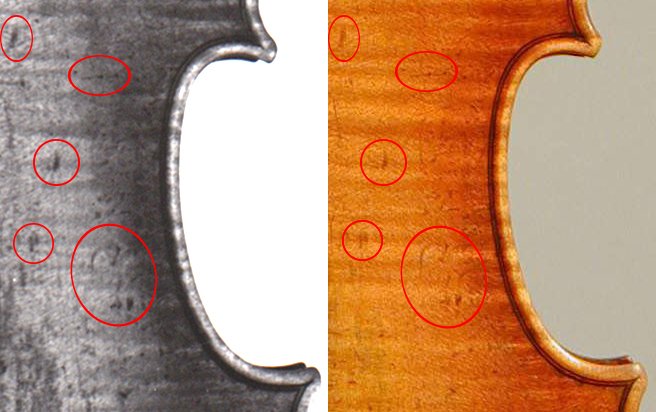

Like a fingerprint, violins have unique details, including the wood grain and its summer and winter growth, the flame pattern on the maple back, nicks and dings from centuries of use, the violin’s torso outline, its carved f-holes, scroll, inlaid purfling, and other distinct features of the maker's work. A comparison of pre-theft photographs of the missing 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin with color photos taken in 2000 of a violin now referred to as the "1707 Stella" Stradivari violin (and c. 1707), indicate a match. Several violin experts have confirmed this match. Comparisons are provided below:

Black and white pre-theft photographs of the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin (Photos: Mendelssohn-Bohnke Papers). Color photographs of the violin now referred to as the "1707 Stella" Stradivari violin (and c. 1707), 2000 (Photos: Tarisio).

Image comparison of the left flamed maple upper bout: Left: Pre-theft photograph, 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin (Photo: Mendelssohn-Bohnke Papers). Right: Color photograph of the violin now referred to as the "1707 Stella" Stradivari violin (and c. 1707), 2000 (Photo: Tarisio). Red markings added for comparative analysis.

Image comparison of the right spruce lower bout: Left: Pre-theft photograph, 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin (Photo: Mendelssohn-Bohnke Papers). Right: Color photograph of the violin now referred to the "1707 Stella" Stradivari violin (and c. 1707), 2000 (Photo: Tarisio). Red markings added for comparative analysis.

Image comparison of the right flamed maple c-bout: Left: Pre-theft photograph, 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin (Photo: Mendelssohn-Bohnke Papers). Right: Color photograph of the violin now referred to as the "1707 Stella" Stradivari violin (and c. 1707), 2000 (Photo: Tarisio). Red markings added for comparative analysis.

“I grew up hearing about this violin and its theft, and it always upset my mother [Lilli Bohnke-Rosenthal] when the subject came up. Most of us in the family thought the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin had been destroyed since its theft from our family’s bank safe in Berlin as a result of Nazi era events. My uncle Walther Bohnke was among those who never gave up trying to find it though. It was always known in our family as my grandmother Lilli’s violin, and it is a vital piece of our Mendelssohn-Bohnke’s family’s heritage. It connects us to our past in very profound and emotional ways.”

Before it was stolen, the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin was in the instrument collection of Franz von Mendelssohn (1865-1935), who reportedly gave this violin to his daughter, Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke. The details of Franz's purchase of this Stradivari are not yet known, but Lilli appears to have played this violin in the 1920s. Both Franz and Lilli were violinists. Franz was also an avid instrument collector, as well as a partner in the Mendelssohn Bank in Berlin and a leader in his community.

Left to right: Franz von Mendelssohn, Ursula Hildebrandt, Emil Bohnke, and Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke (undated). Photo: Joël-Heinzelmann (Mendelssohn-Bohnke Papers).

Lilli and her husband, Emil Bohnke (a violinist, violist, composer, and conductor), met a tragic death in 1928, leaving behind three very young children, Robert-Alexander, Lilli, and Walther Bohnke. Robert-Alexander later recalled,

"After the death of my parents, my two older siblings and I grew up with our grandparents Marie and Franz von Mendelssohn in Berlin. My grandfather was a banker and president of the Chamber of Commerce, but he played the violin every evening if possible, in earlier years (before I was born) very often string quartets with Joseph Joachim, who was one of the musical household gods of our family, later quartets, trios and duos with Arthur Schnabel,... with my godfather Carl Flesch,... with Edwin Fischer... and also with... Albert Einstein."

— Robert-Alexander Bohnke, Das deutschsprachige Klavierperiodikum. Piano-Jahrbuch. Vol. 3, Recklinghausen, Piano-Verlag, 1983, pp. 186-94; 189-90.

Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke and Emil Bohnke's three children: Walther, Lilli, and Robert-Alexander, c. 1929. Photo: Joël-Heinzelmann (Mendelssohn-Bohnke Papers).

Franz and Marie von Mendelssohn were considered Jewish by the Nazi regime. On May 28,1934, Franz indicated to British violin expert and dealer, Alfred Hill, that his family was unable to get their Stradivari instruments out of Germany, Alfred noted that Franz appeared to be "feeling the stress of circumstances," and "if the present Regime dared to do it, they would take possession of all the wealth of these rich Jewish families." (Diaries of Arthur Hill, Private Collection).

With Franz's death in 1935, Marie became the guardian of the Bohnke children. Because the Mendelssohn Bank was considered a Jewish business under the Third Reich, the bank was forced into liquidation on December 1, 1938, with many of its assets acquired by the Deutsche Bank. As a result of Jewish persecution, the Mendelssohn family's real estate on Jägerstrasse was sold under duress, as was their home on Herthastrasse where Marie von Mendelssohn had lived with the three Bohnke children.

The 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin was secured in a safe on Mendelssohn property at Jägerstrasse 51, Berlin, for many years, according to the Mendelssohn Bank's insurance documentation and other historical records. After Jägerstrasse 51 was taken over by the German Ministry of Finance, the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari and other rare instruments owned by the Mendelssohn Bohnke family were moved to a bank safe rented by the Mendelssohn Bank in Liquidation in the Deutsche Bank, Berlin. Nazi-era German law and court appointed non-family legal guardians for Robert-Alexander Bohnke (who was a minor) appear to have prevented evacuation of the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari (and a second violin) to a safer location in or about 1944.

After World War II, the Mendelssohn Bank in Liquidation confirmed to Walther Bohnke that the bank safes it rented in the Deutsche Bank in Berlin were plundered. The 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin and another violin were secured in one of these banks safes. Soviet troops arrived in Berlin in late April 1945, with heavy shelling and fighting in the streets. Two days after Hitler's suicide on April 30, 1945, members of the Russian Army took control of the Deutsche Bank and looting followed. It is unclear if the theft of the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari took place before the Soviet occupation of Berlin, or after. The identity of the thief, his or her motive, and the precise date of theft are currently unknown.

Walther Bohnke placed stolen property reports in German and English publications in 1958, seeking the return of the family's 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari, with identifying photographs. It took fifty years for this violin to emerge from the long shadow of the Nazi era in Paris in 1995, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, German reunification in 1990, and dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Walther Bohnke continued to report the family's loss, filing a claim with the German Ministry of the Interior in 1993 (Claim No. 1 0 045-93 and Reference No. KII 3 (b) 331 133/RUS), a file that was later transferred to the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media (Reference No. K 13 331 133-3/140), and the German Lost Art Foundation. The theft of the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin has also been reported by the Mendelssohn-Bohnke family to the Berlin State Criminal Police Office, File No. 250123-1307-256882, and Berlin State Prosecutor, File No. 252 UJs217/25.

One Stradivari, Two Identities

The 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin is the same violin as the instrument referred to as the 1707 "Stella" Stradivari violin. The earliest record located to date that mentions the "Stella" is a March 31, 2005 provenance statement on the business letterhead of Paris luthier Bernard Sabatier written in French, which Mr. Sabatier denied having written and stated was falsely attributed to him. This statement was translated into English and German on the letterhead of Austrian violin dealer Dietmar Machold and attributed to Bernard Sabatier. This March 31, 2005 statement, fiction or fact, has become the "Stella" Stradivari's origin story. The evolving violin dealer business records located to date for this violin contribute to an understanding of its history.

There were only two pre-theft violin dealer records in the Mendelssohn-Bohnke file regarding the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari: a November 30, 1930 appraisal and a certificate of authenticity of the same date prepared by German violin expert and dealer, Philipp Hammig. In Mr. Hammig's 1930 certificate he stated that the date on the internal label read "1709." The Lost Music Project located additional Hammig business records in a private collection in Germany in 2017 with two entries for this Stradivari that also used the "1709" date (report link below).

It was not until June 20, 2024, that the Lost Music Project discovered the whereabouts of the missing 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari as a result of a clue that the violin might be in Japan. A search of the Japanese Internet looking for references to Stradivari violins with the date 1709 and the name Mendelssohn brought no results. Additional searches were conducted for Stradivari violins with other dates and names, focusing on the unique characteristics of the missing violin reflected in the pre-theft black and white photographs. A match was finally found with the surprising result that the missing 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin was referred to instead as the 1707 so-called "Stella" Stradivari violin. The online entry in Japanese stated that the name "Stella" had come from a prior owner who allegedly had commented that the violin's sound shined like a star and that the French family who purportedly once owned it had fled from France to the Netherlands during the French Revolution and survived in exile with the violin for generations.

The long disappearance and private possession of the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari since its theft, as well as its alternative name, date, provenance and history made it difficult to detect.

The Historical Dealer Records for the "Stella" Stradivari

Once the Lost Music Project discovered that the missing 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari had been moving in the stream of commerce under an alternative identity, an entirely different array of historical dealer records for the "Stella" Stradivari were analyzed. These records led to new facts and witnesses, and a cautionary tale about the importance of provenance evidence.

After the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari's theft from a safe in the Deutsche Bank in Berlin, it appears to have passed from seller to buyer without any Mendelssohn provenance. The violin surfaced in Paris in 1995.

1995:

The earliest post-war account of the whereabouts of this missing violin comes from French luthier, Bernard Sabatier. He encountered the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin in 1995 when a Russian violinist allegedly brought the violin into his atelier on the rue de Rome in Paris to sell. At the time Mr. Sabatier was not aware of the violin's provenance. But in June 2025, the Russian violinist allegedly told Mr. Sabatier that he purchased this violin from a German violin dealer doing business in Moscow in 1953. The names of the German dealer and the Russian violinist have not yet been provided by Mr. Sabatier, but these questions have been asked.

In an effort to authenticate the violin in 1995, Mr. Sabatier reached out to internationally esteemed British violin expert, Charles Beare (1937-2025), then of John & Arthur Beare Limited in London, to obtain his opinion. As a result of Mr. Sabatier's meeting with Charles Beare with the violin in hand, J. & A. Beare prepared a certificate of authenticity dated February 1, 1995, stating, in part, that the violin was "made under the direction of Antonio Stradivari of Cremona by his son Omobono." A detailed description of the violin followed and a comment that the "violin is a fine and characteristic example of the maker's work showing many of his father's qualities" and measuring "35.5 cm in length of body, with widths of 16.7 cm and 20.cm.” The certificate was issued with color photographs of the violin, with front, back, and side views. Regarding the date and the internal label, this 1995 certificate states, "It dates from c. 1705-10 and bears a label of Antonio."

1997:

A May 6, 1997 letter to Mr. Sabatier written on J. & A. Beare letterhead with Charles Beare's signature states, in part: "[w]ith regard to the violin by Stradivari which you are currently offering for sale it would, in our opinion, be correct to describe it as a joint production by the celebrated Antonio Stradivari in collaboration with one of his sons." Mr. Beare described the violin as "a fine example in good condition, dating in our opinion from about 1707, and the quality of its tone is thoroughly characteristic of the period of its manufacture," which Mr. Beare described as "Stradivari's 'Golden Period.'“

In 1930, the date on the violin's internal label read "1709," according to Berlin violin expert Philipp Hammig, who appraised, certified, and maintained this violin for the Mendelssohn family. But in the late 1990s various experts interpreted the date on the label as "1707." Stradivari's labels at this time had only the first digit preprinted; the maker added the remaining three numbers with his pen. A handwritten "7" might look like a "9" when peering through the bass side f-hole into the cavity of the violin body at a nearly 300-year-old label. It is unclear if the condition of the internal label may have changed over time (intentionally or not). Internal label dates are subject to varying interpretations, errors, and tampering.

1999:

In 1999, Mr. Sabatier prepared a certificate of authenticity for this Stradivari violin, with photographs. His certificate quoted the label as stating: "Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat anno 1707." He noted that the violin was an authentic work by Antonio Stradivari with the scroll showing the hand of one of Antonio Stradivari's sons. A handwritten notation amid the photos says, "Antonio Stradivari Crémone 1709." An English translation of Mr. Sabatier's 1999 certificate of authenticity was prepared on the letterhead of Austrian violin dealer Dietmar Machold.

According to Mr. Sabatier he sold this Stradivari violin on behalf of his Russian customer through luthier and dealer Claude Lebet. Payment to the Russian violinist for the Stradivari and a commission to Mr. Sabatier for his efforts were not made in one payment but through the sale of several lesser valued instruments provided to Mr. Sabatier through Mr. Lebet. The sales price received by the Russian violinist for the Stradivari violin has not yet been provided by Mr. Sabatier, but this was reportedly a low price for the Stradivari.

Sometime between 1995 and 2000, the violin was reportedly next sold to "Pierre Huguinin" of Neuchâtel, the date of sale is unclear.

2000:

On September 20, 2000, John & Arthur Beare wrote another certificate of authenticity for this violin, which stated that the label it bore was dated "1707." In November 2000, the Stradivari was offered for sale by Tarisio Auctions in New York as an unnamed "rare and important violin made under the direction of Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, c. 1707," and labeled “Antonio Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat Anno 1707.” Rare instruments of the violin family are often named after prior owners, players, or another name, for example, "the Apollo." The violin did not sell at auction. A private sale reportedly took place in 2000 to an "unknown" owner.

The March 31, 2005 "Stella" Stradivari Provenance Statement

On March 31, 2005, a provenance statement was written for the "Stella" Stradivari violin on Bernard Sabatier's letterhead and attributed to him. However, on June 17, 2025, Mr. Sabatier denied that he authored this provenance statement and indicated that it was falsely attributed to him.

This 2005 provenance statement says that the "Stella" Stradivari violin was "in the possession of a noble family which has been living in Holland since the times of the French Revolution" and that a "remote ancestor" of this family had named the violin "the Stella," because the violin's sound "twinkled like a star." There is no mention of the Mendelssohn name in this provenance statement; it is unclear what, if anything, the author of this statement knew of this. The Mendelssohn name arguably would have increased the violin's sales price.

Two translations of this provenance statement in English and German appear on the letterhead of Austrian violin dealer Dietmar Machold. Mr. Machold also appears to have written three certificates of authenticity for this Stradivari violin in 2004 and 2005. The last is dated August 17, 2005, in which the violin was reported to be in the possession of Mr. Eijin Nimura of Tokyo.

[updated August 7, 2025] On July 28, 29, and August 5, 2025, Mr. Dietmar Machold contacted me via email. Mr. Machold denied authorship of the March 31, 2025 provenance statement in an email dated July 29, 2025, in which he stated, in part: “The certificate of Mr. Sabatier and the history of this violin we translated from French into English on our ‘Machold Rare Violins’ stationary, indicating clearly in writing that the original text, in this case French, was from Bernard Sabatier….” Mr. Machold stated on July 28, 1925 via email, “In 2004, I got this violin as the ‘Stella’ Stradivari from 1707 on consignment from Bernard Sabatier…. Subsequently, I received the documents related to this violin in order to complete the sale, including the history of the ‘Stella’ violin, written from Sabatier on his stationary, dated March 31, 2005. The history was in French and so I copied the exact and correct English translation under the letterhead of Sabatier….” Mr. Machold has also advised in his emails that his employee, Keith Bearden, working in Tokyo, “was handling all of our sales in the greater Asia/Pacific region….” Keith Bearden’s history in the violin trade has been the subject of prior reporting.

On October 21, 2024, and on several occasions thereafter, efforts were made to contact Mr. Nimura in order to communicate and find a cooperative solution to the unresolved theft of the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin. The Mendelssohn-Bohnke family remains hopeful that a collaborative discussion will take place.

Note on the status of research and the Preliminary Report on the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin:

Evolving research continues to result in new information and historical records regarding the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin. The Preliminary Report (link below) should be considered a working document that will likely be updated in the future as information and records continue to be located, which might shed light on issues of ownership, theft, authenticity, provenance, and other pertinent topics.

The Preliminary Report on the 1709 Mendelssohn Stradivari violin is being made publicly accessible at the request of the Mendelssohn-Bohnke family.